Thirty-five years ago this month, Stereo Review dedicated its June 1986 issue to a look at good ol’ American-made audio. It was the first in a series of three issues, with following looks at the Japanese and European markets in subsequent months.

Clockwise from lower left: the Klipsch Fortes; the Bose 10.2; Boston Acoustics’ A40; Polk Audio’s SDA Compact; and AR’s MGC-1.

“From time to time, a reader writes in to request a list of American audio equipment manufacturers so that he can ‘buy American.’ We’ve never supplied such a list because ‘buying American’ is tricky,” Stereo Review Editor-in-Chief William Livingstone explained in that month’s editorial. Do you give more support to the labor force and overall economy of the United States by buying a component manufactured in Hong Kong for an American company or by buying one made by American hands in a Japanese-owned factory in California or Tennessee?

“We don’t have an answer to that question and have never based our buying advice on the country of origin of equipment. Like the vast majority of our readers, we are most interested in what a component does, how well it does it, and whether it represents good value at its price.

“Still, there is so much talk about technological agendas, balance of payments, the ‘hollowing’ of American industry, and so forth that we have decided to focus three issues on the state of audio in the United States, in Japan, and in Europe. We are beginning in this issue by examining our own nation’s audio. Reflecting the interests of our readers, we are leaning more heavily on technology and products than on manufacturing and marketing.”

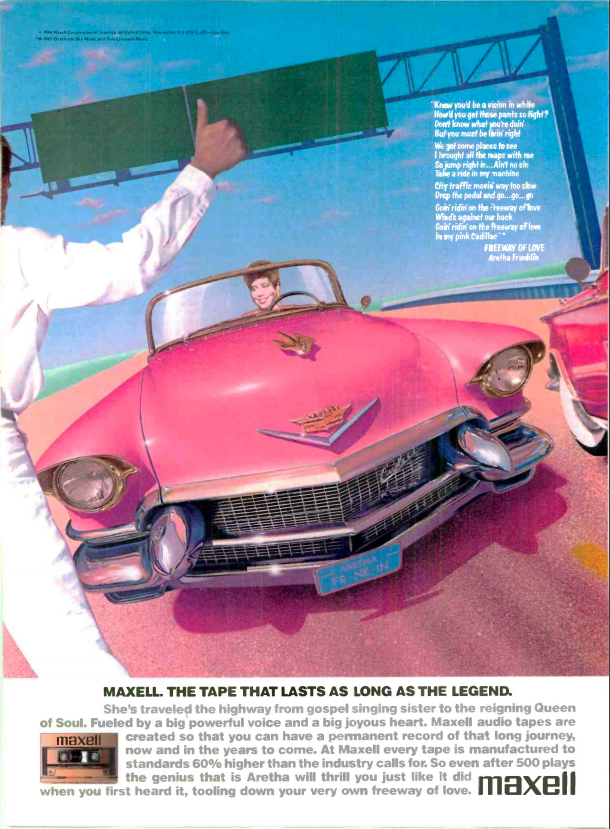

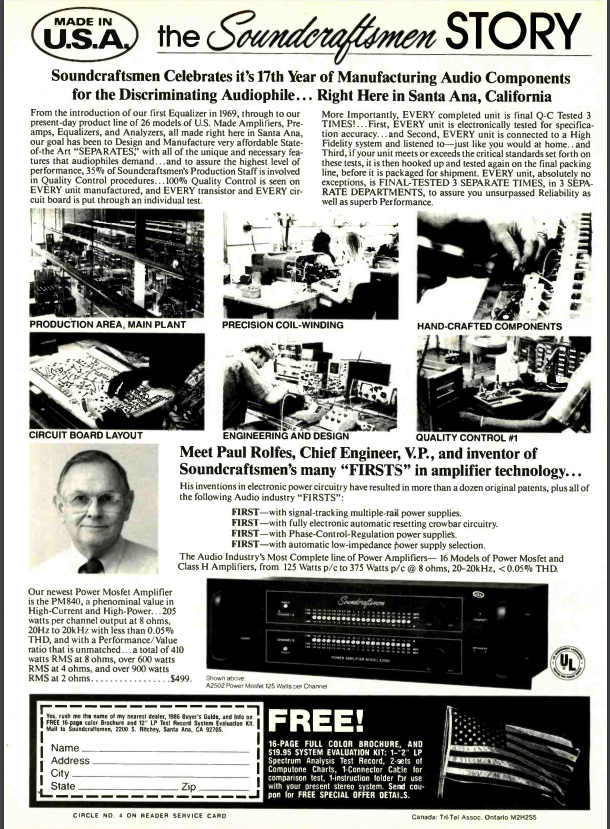

The highlight of this coverage was a Steve Birchall article entitled “The State of the Nation’s Audio,” which we’ve transcribed for you in full here, and included a heaping helping of those vintage ads you love oh so much.

The State of the Nation’s Audio

Innovative design and superb craftsmanship keep America at the forefront of technology

by Steve Birchall

American audio is enjoying a new surge of growth, stimulated by a surprisingly rich selection of new hi-fi consumer products. Many product categories, such as Compact Disc players, audio-video receivers, and hi-fi VCR’s, have come into existence only recently. New technologies, interacting with changing trends in music and allied arts, are leading to new forms of entertainment such as music videos, interactive CD’s, and the illustrated CD. Some television programs have hi-fi sound now, as stereo broadcasts become available to more and more people. As a result, the demand for good audio equipment is also increasing. Excitement is in the air, because audio is on the move again.

The Compact Disc and stereo TV are playing a major role in generating excitement about hi-fi. Suddenly, audiophiles are appreciating the sheer joy of listening to music more than ever, and untapped audiences for hi-fi are being awakened for the first time. The clean, clear sound of a CD immediately wins over first-time listeners through its audible excellence. And imagine how enjoyable this year’s miniseries extravaganzas will be in hi-fi stereo.

But where does the American audio industry fit into all of this? While much of the equipment seems to be made in Japan, and you can’t buy a receiver made in Pittsburgh, or a tape recorder made in Albuquerque, American manufacturers have carved impressive niches for themselves in the audio marketplace, especially in the areas of psychoacoustics (speakers) and high-end equipment. They are doing what the European auto industry did in response to American success in mass-producing of cars: concentrating on quality, not quantity.

Many American audio companies are small, with only a handful of employees led by a senior engineer, a “master craftsman” of audio technology with a strong personality, who watches over every stage of production. The sophisticated equipment made in these shops always has the special touches and style of the man behind it, a tradition that began with men like Avery Fisher and H. H. Scott and is flourishing today in the work of people like Matthew Polk and Bob Carver. The result? Innovatively designed, superbly crafted equipment that places Americans at the forefront of audio technology.

In contrast, most manufacturers in the Far East concentrate on mass producing audio equipment at low cost. From them, we get the basic Fords, Plymouths, and Chevrolets of audio. But in response to the question of how American companies compete with the Japanese, Threshold’s Nelson Pass replied, “I don’t consider them competition. In fact, they make better customers than competitors.” Affluent Japanese who value good sound buy Threshold amplifiers for the same reasons affluent Americans buy Mercedes automobiles.

Present Accomplishments

Currently, some of the most exciting and innovative developments in American audio technology are concentrated in broadcasting – an industry where audio advances are slow to take shape. Multichannel television sound (MTS) has given TV a stereo audio signal with hi-fi quality. As a result producers are paying close attention to the dramatic effects of sound in TV productions. Even played through an average hi-fi system, a TV show with a good soundtrack can be very exciting.

Heading the group responsible for the development of stereo TV was Les Tyler, vice-president of engineering for the American company dbx. Like the established system for broadcasting stereo FM programs, the new stereo TV system involves two separate signals, which are decoded in appropriately equipped receivers. One signal represents the sum of the left and right channels (L + R), and is thus equivalent to mono, and the other represents the difference between them (L – R). The MTS system broadcasts the mono signal using frequency modulation but the difference signal with amplitude modulation, and dbx noise reduction keeps reception quiet.

Several designers have developed circuits to reduce the noise of FM stereo at the receiver. Larry Schotz of LS Research has developed a circuit – which he keeps improving – that reduces noise by blending the stereo channels in a dynamic fashion. The blending is controlled by the program’s moment-to-moment frequency content and modulation level and by the strength of the received signal. Although this system reduces separation together with noise, the effect of the blending is inaudible except in its hiss reduction. Schotz circuitry is included in products from Proton, NAD, and others.

Bob Carver of the Carver Corporation has designed receivers and tuners featuring a circuit that uses program information in the relatively quiet mono FM signal to synthesize a low-noise difference signal with compatible frequency and amplitude characteristics. Under noisy conditions the synthesized difference signal smoothly and automatically replaces the actual broadcast difference signal.

The latest approach to the problem of making the noise level and range of FM stereo equal to mono reception is FMX, the brainchild of Emil Torick at CBS Technology Center. Like most noise-reduction systems, FMX is a companding process that compresses the difference signal at the transmitter and then expands it at the receiver, restoring the original information together with a 20-dB noise reduction. Unlike other noise-reduction systems, FMX is entirely compatible with the existing stereo broadcast system and will not interfere with reception by existing receivers. FMX decoders are inexpensive to manufacture, so the prices of new receivers should not increase dramatically. According to Julian Hirsch and others who have heard demonstrations of FMX, the results are excellent.

Digital techniques are finding broadcast applications too. In Boston, WGBH uses the dbx 700 digital audio processor for live broadcasts of the Boston Symphony. The processor serves as a noise-reduction system in the microwave link from Symphony Hall to the transmitter, and the improvements in clarity and detail are substantial. Recently the dbx 700 was used for the first nationwide live digital broadcast on National Public Radio. The occasion was an all-Ravel concert by the Swiss Romande Orchestra at MIT’s Kresge Auditorium. The digitally encoded signal went by microwave to the NPR satellite uplink and was received across the country by about a dozen stations equipped with dbx 700 decoders. (As with digital tape recording, broadcasting the digital audio signal requires the bandwidth of a TV channel.) For the stations not equipped with decoders, NPR used the regular audio channels on the satellite.

This high-quality audio transmission technique will become important for TV broadcasting too. Combined with the MTS stereo audio signal, it could make music on television sound spectacularly realistic in your home. Programs such as Live from Lincoln Center would have incredible clarity, as would any imaginable music program, from a live Christmas Eve concert or the Grammy Awards Show to the rededication ceremonies for the Statue of Liberty with the Boston Pops on the Fourth of July.

American CD Players

Through Philips in the Netherlands and Sony in Japan, other countries got a head start in making Compact Disc players, but American companies are contributing in this field by refining the technology and manufacturing procedures.

Paul McGowan, president of PS Audio, criticized Japanese CD players in a New York Times article (January 30, 1986): “The real problem is that they’ve surrounded all this Buck Rogers technology with parts no better than you find in a Japanese transistor radio.” McGowan’s company modifies a stock Philips 2040 CD player by replacing all the analog circuits and beefing up the power supply. PS Audio inserts a passive analog pre-filter to remove the high-amplitude spikes at 176 kHz that can trigger an operational amplifier into producing transient intermodulation distortion (TIM). They replace the integrated-circuit (IC) op amp with one made from discrete circuitry to eliminate that source of distortion completely. The entire audio circuit has no capacitors in the signal path.

McIntosh is building CD players using Philips transports and digital circuits. But the rest is all McIntosh, rather than a rebuilt Philips player. According to Gordon Gow, the company was concerned that, in comparison with a good turntable, tonearm, and cartridge system, a CD player’s high end was a bit too harsh. To combat this problem, engineer Sidney Corderman designed an analog filter to remove ultrasonic intermodulation products.

The work of both these companies exemplifies what many U.S. audio manufacturers are doing. They are very particular about the quality of the parts they use, and they are finicky about refinements of circuit design. They don’t use an IC chip simply because it’s expedient. They use it with knowledge of its characteristic distortion – and how to overcome it. They use capacitors where they help and keep them out of the signal path. That kind of approach to design and construction leads to the excellent sound of American audio equipment.

Speakers

Perhaps the single most significant American contributions to audio technology have been in the area of speaker design and the study of psychoacoustics. It’s difficult to forget the work of men like Edgar Villchur (Acoustic Research), inventor of the acoustic-suspension system and the dome tweeter, Amar Bose, with his Direct/Reflecting speaker system, and Paul Klipsch, with his horn-loaded speakers. Pioneering work also came from companies such as Advent, Infinity, JBL, Ohm, Theil, and Allison.

American research in psycho-acoustics has led to products like Matthew Polk’s Stereo Dimension Array (SDA) speakers, Mark Davis’s dbx Soundfield speakers, Jim Thiel’s time- and phase-coherent speakers, and Ken Kantor’s Acoustic Research Magic speaker with its delayed ambience subsystem. Other advanced designs have come from Acoustat, Snell, Dahlquist, Fried, and Boston Acoustics.

American speakers have also benefitted from advanced construction techniques. New materials including high-temperature glues and a variety of lightweight cone materials such as titanium and polypropylene have helped to improve speaker performance. ADS, for example, uses more than thirty different kinds of adhesives, each for a different purpose, according to marketing vice president Larry Daywitt.

The dbx Soundfield speaker gives special attention to the problems of off-axis radiation; a listener can walk around the room and the stereo image will remain stable. Matthew Polk created speakers with lifelike three-dimensional imaging by giving attention to details of cabinet-edge reflections and phase information. Jim Thiel achieved a time- and phase-coherent speaker through sloping baffles and synthesized first-order crossover networks. Ohm speakers incorporate the work of the late Lincoln Walsh, who theorized that a speaker’s radiating surface does not really behave like a piston, nor can it be made to. Rather, he said, it behaves like a perfect wave transmission line.

Timothy Holl – now at Bose, previously at Wharfedale and Acoustic Research – observes that speakers are converging on the same kind of sound. According to Holl, “The search for the neutral speaker inevitably leads to the same results.” The world market for speakers also has caused some of the uniformity, because a good speaker sells well everywhere. In the United States, the old distinction between East Coast and West Coast speakers is nearly gone. As speaker design becomes more rational, everyone is able to approach that elusive ideal: neutral sound quality.

Yankee Ingenuity

The basic technology for digital audio is essentially American in origin. Philips and Sony applied that knowledge to develop the Compact Disc, but they could not have done it without American computer technology. Bell Labs has been a fountain of key developments, including the work of Claude Shannon, who founded the science of information theory, and John Nyquist, whose famous theorem established the minimum sampling rate needed to define a frequency.

Another contribution from Bell Labs was the transistor. Without the benefits of the transistor’s low power consumption, small size, and cooler operation, most of the electronic products we now enjoy would not exist. Try building an all-tube CD player, if you don’t believe that! The next development up the solid-state ladder was the integrated circuit, developed by Fairchild and Texas Instruments. Without IC chips, CD players would be the size of refrigerators.

The laser, too, is the product of many American researchers (even Alexander Graham Bell proposed transmitting sound on modulated light waves). The cross-interleave Reed-Solomon error-correction code used by CD’s was originally intended for telemetry data from deep-space probes. The spectacular pictures we’ve received from Uranus, Saturn, and Jupiter are good examples of that technology in a visual application.

In short, American audio technology has made the digital revolution in audio possible. Without American scientists’ driving curiosity and enterprising spirit, audio in every country around the world would be quite different today.

“Not with a Bang …”

But there is a dark side to all of this success, past and present. In the view of many observers, including Sony chairman and co-founder Akio Morita, America is losing its ability to manufacture consumer goods. Morita, quoted in the March 3, 1986, issue of Business Week, calls this a “hollowing of American industry.” Tomlinson Holman, who was chief audio engineer at Advent, was a co-founder of Apt, and now is conjuring audio effects at Lucasfilms, pointed to the “retreat into the high end” and observed that American investors are not interested in hi-fi equipment manufacturing.

Andy Petite, of Boston Acoustics, echoed this point of view, citing the “demise of support industries,” particularly chip makers, in the U.S., and the “gradual shift of electrical manufacturing in general” to other countries. Threshold’s Nelson Pass noted that the same amount of silicon goes into one of Motorola’s output transistors as its 68020 computer chip. Because the demand for the 68020 is greater, and the profits are greater, Motorola doesn’t make as many output transistors.

The tendency of American companies to market imported goods has led to an erosion of audio design work in the U.S. Les Tyler of dbx observed that his company is one of the few that still maintain a large design staff. When the practice of foreign manufacturing first began, an American company would design the equipment and have it made to its specifications. Today, an American company is likely to buy existing equipment, already designed by a foreign manufacturer, and simply put its own logo on the product. The function of the American company is little more than to market the product.

New communications media, from Edison’s cylinder and silent movies, to the telegraph and telephone, to radio, television, and satellites, have tied nations and people together in increasingly complex ways. As a result, manufacturing and consumption tend to spread evenly around the planet.

At ADS, speakers contain parts from all over the world – American drivers, Japanese crossover coils, and German cabinets. The University of Michigan is making a study of ADS to see how and why the company has been so successful with its international approach. But ADS is not alone in the idea of a “world speaker.” If you look inside just about any piece of audio equipment, you’ll find parts from all over the world.

Another way that business and industry disperse internationally is through reinvestment. Japanese and German companies are building cars in America, Sony builds TV sets in San Diego, TDK has a blank-tape plant in Irvine, California, and Sony operates a CD pressing plant in Terre Haute, Indiana. Philips and DuPont recently signed an agreement to build CD pressing plants in several countries. The first will be in the U.S., in North Carolina. Many American companies are licensing their inventions to foreign manufacturers. For example, Yamaha uses Carver circuits in its power supplies. Nakamichi uses Nelson Pass’s Stasis circuits in its amplifiers. Many cassette decks contain both Dolby and dbx noise-reduction circuits made under license.

The Future

The American audio industry has had its ups and downs in the last couple of decades and has had to make a variety of adjustments to changing market conditions. But American audio technology has never wavered. It is now moving beyond the hi-fi industry and into some completely new fields.

Current research involves artificial intelligence, voice recognition, speech synthesis, and, most important, new applications of psycho-acoustics made possible by digital signal processors.

Ray Kurzweil of Kurzweil Music Systems, Inc., speaking at the Boston Computer Society, demonstrated an advanced music synthesizer, a voice-activated word processor, and a voice-activated database manager. Imagine talking to your typewriter and watching the words appear on the paper. Some of these products may reach the market before the end of the year!

Kurzweil’s music synthesizer stores instrument definitions in large read-only-memory (ROM) chips and uses artificial intelligence to turn the data into realistic sounds. The “bite” of the bow against the strings is hair-raisingly real. The piano sounds better than some conventional pianos, and it is cheaper to make. But the real prize of the synthesizer is the intelligent sequencer (on -board digital recorder). At the BCS meeting, a musician used it to create a lively Dixieland combo for the audience.

Voice-activated remote controls will become quite common as the technology is refined and put onto microchips. Combine this with speech synthesis, and your system could respond in various ways. Of course, manufacturers would give their equipment “personalities” to make them more user-friendly. Some day soon you might say, “Murphy, turn on the VCR at 8:30 on Channel 25, and stop it at 10:30.” The system would answer, “Okay, Bill, but the tape in the machine only has thirty minutes left, so you need to put in a new tape.”

New work in psycho-acoustics will lead to better speakers. Current tests and measurements don’t tell enough about how speakers really sound. Phase response in the crossover region, power radiation into a real room, and other related characteristics currently are receiving a lot of attention. Digital signal processors will lead to new speakers with much more realistic spatial illusions than present speakers produce. Bob Carver is about to introduce a new speaker, only two inches thick, with holographic imaging capabilities (though not using the same circuit as his Sonic Hologram Generator).

In electronics, too, many measurements are becoming obsolete, and new specifications will replace some of the current ones. Parameters are being more closely defined, and it will become harder for careless designers to measure only what is convenient to measure while overlooking characteristics that control actual performance. The search for rational definitions of performance is an important contribution to the high quality of American equipment.

Other engineers are looking for better digital-to-analog (D/A) converters. The successive-approximation method now used is not necessarily the best. The design group at dbx is developing new types of D/A converters with lower distortion. They are also looking for better-sounding anti-aliasing filters and developing 18-bit converters for greater resolution.

In amplifiers, Threshold’s Nelson Pass is moving on from his critically acclaimed Stasis amplifier and is working on a pulse-width-modulation power amp and digital-switching power supplies. Bob Carver is using his proprietary Magnetic Field circuitry to develop new lightweight, high-power amplifiers. William Johnson of Audio Research is constantly improving his all-tube designs, and innovations can always be expected from people like Larry Schotz, Tomlinson Holman, Ralph Yeomans (Soundcraftsmen), David Hafler, Mark Levinson, and companies such as Crown, Adcom, Counterpoint, and Acoustat.

A few years ago, Acoustic Research demonstrated the Adaptive Digital Signal Processor, which analyzed the colorations created by the interactions of a speaker with a room. Unlike some of today’s self-adjusting graphic equalizers, it included the reflections in the room and even from the cabinet edges in its analysis. It then created an inverse filter to undo these effects. In those days, it was too expensive to be a practical product, but, as Les Tyler recently observed, it could become a practical consumer product now. And once you remove the walls of the listening room, what’s to stop you from putting in the walls of any other room? If you don’t like the acoustic ambience of a recording, you could take the orchestra out of Carnegie Hall and put it into the Amsterdam Concertgebouw.

An audiophile of the not-too-distant future might say to his voice-recognition controller, “Murphy, this performance is terrible. Put that orchestra into a hockey arena.” The system might answer back, “Okay, Bill. Do you prefer the arena in Minneapolis or the one in Montreal?”