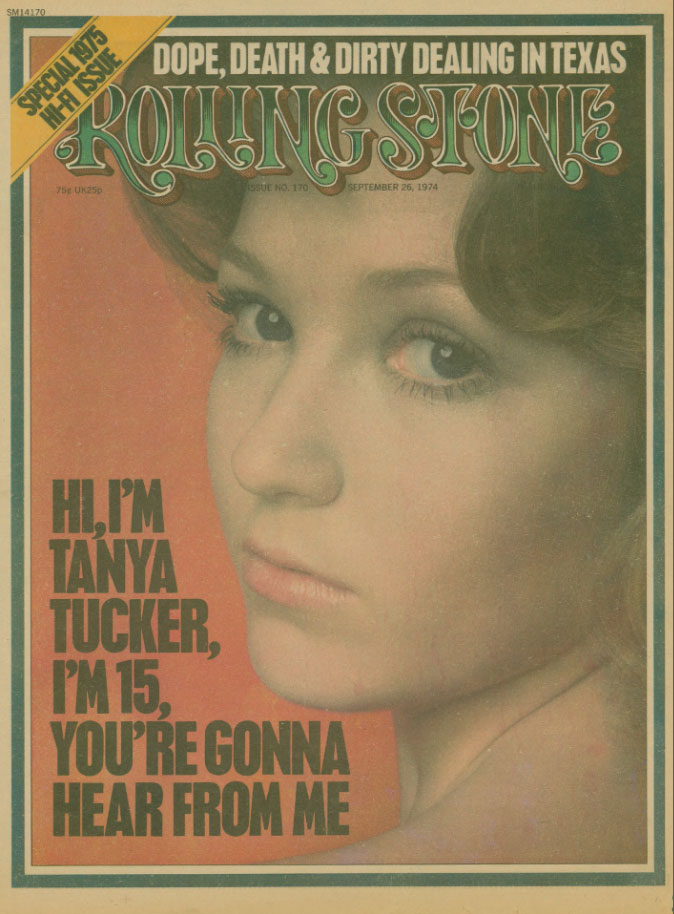

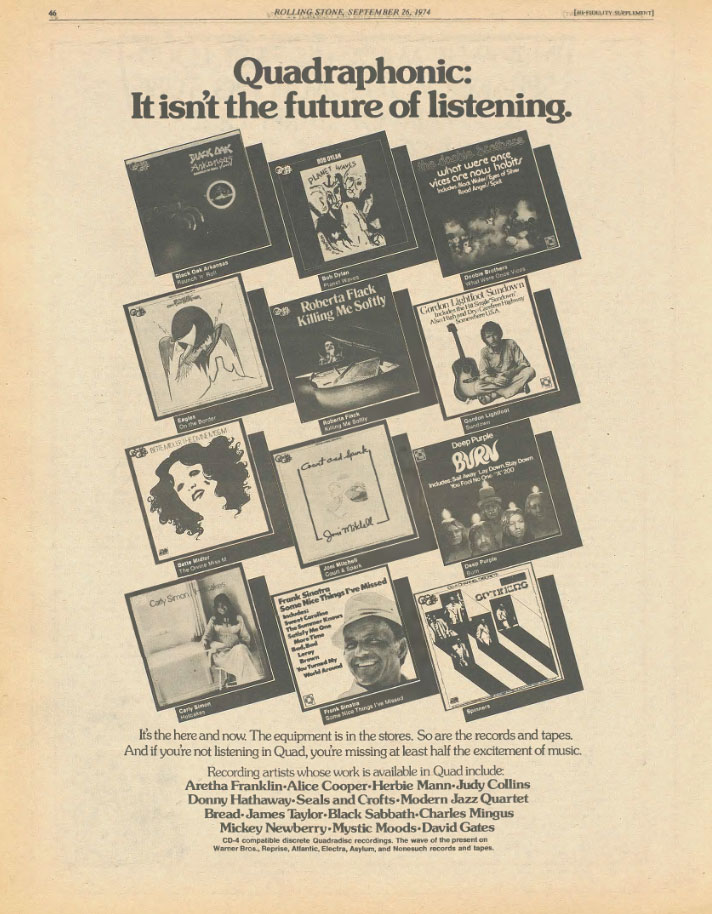

It’s time to flip through another tattered magazine and look at some vintage tech and music trends of the past. This month, we’ll flip through this September 1974 issue of Rolling Stone, featuring the debut of their yearly hi-fi buyers’ supplement.

Rolling Stone was still very much THE voice of the counterculture in 1974. They hadn’t gone glossy yet. You could still buy drug paraphernalia from the classified ads in the back. But they also had their share of high-end advertisers, particularly from the hi-fi bunch, so it made sense in the fall of 1974 for them to do their first 48-page pull-out supplement dedicated to all things audiophile.

The supplement proved popular enough that it became a yearly feature through the rest of the ’70s, and we’ll revisit successive years in future months. In the meantime, if you’d like to download the whole 1974 supplement in PDF format, we’ve included it for you here.

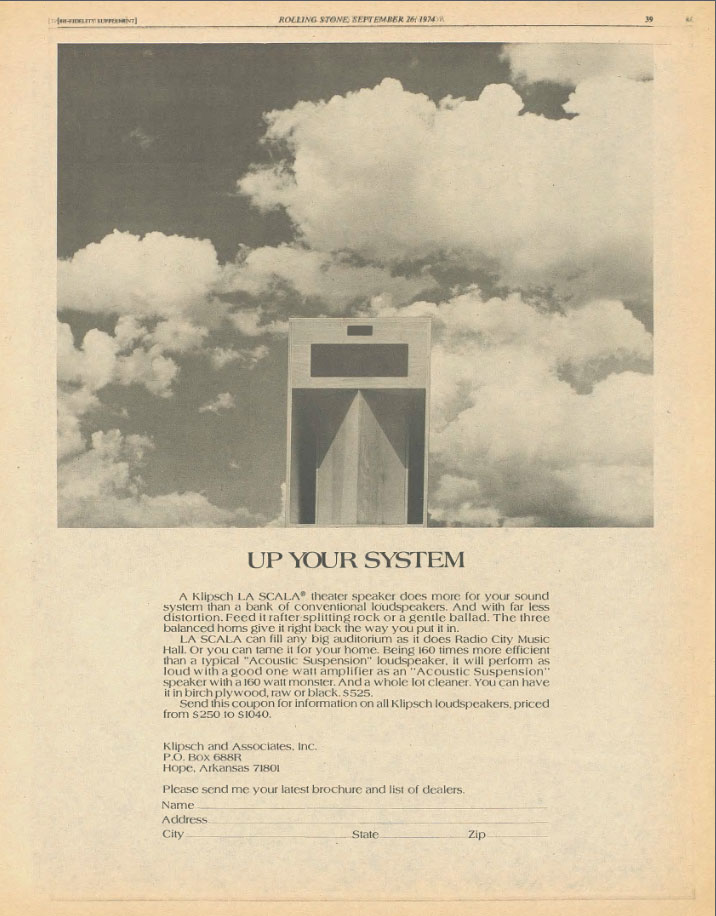

The most interesting part of this supplement is a feature article on Paul Klipsch, “I Have Been to the City of Hope and My Ears Are Wide Open,” written by Tim Cahill, which takes an offbeat look at the eccentric genius who first built loudspeakers out of a shed in Arkansas. We’ve transcribed here in full (apologies for any “Klipschoms” that weren’t caught; converting PDF to text is an inexact science) and supplemented it with some spectacular ads from the same issue. Enjoy!

I Have Been to the City of Hope and My Ears Are Wide Open,” by Tim Cahill

How I came into possession of the two great beasts is an overlong and convoluted tale. Suffice it to say, they take up about a cubic yard apiece of my living space and are remarked upon with some apprehension by guests. One is obliged, in the confines of my flat, to sit no more than a few yards from these monsters, staring directly into the bore, as it were.

More than anything else, l suppose, it is the gaping flat black maws which give the impression that, in irresponsible hands, these Klipsch La Scala speakers are capable of shattering aural cavities and leaving one dazed, unconscious and bleeding from the brain. Not entirely so, of course. More than once in the last few years – for explicable reasons associated with indulgence – I have cranked the La Scalas up past the threshold of pain. And yet … I live. I hear.

Other smaller speakers, given the proper amp, are capable of pounding out more noise. But these Klipsches, how to describe them? Surgically precise: That gives the impression of cleanness, but it also suggests they may be a bit sharp or shrill at high frequencies, and that is not true. At the bottom end, one has no difficulty distinguishing between a closely spaced bass drum beat and a Fender bass note. There is none of that “gutty” sounding extra bass some manufacturers build into the speakers they build for the rock market.

A quick aside: It was the summer of 1956 when I bought my first phonograph, a pathetic portable with a built-in speaker. The saleswoman, I’m sure, marked me for a pimply rube. She put a 45-RPM copy of “Don’t Be Cruel” on the turntable and cranked the bass over to full. Elvis had never, but never, sounded that way on the radio. Some several weeks after I got the phonograph home, it slowly began to dawn on me that I had somehow been taken.

Such was my seminal audio experience, and this coupled with a truly monumental ignorance of acoustics and physics has made me the aural counterpart of the clod who says, “I don’t know anything about painting, but I know what I like.” As a technical incompetent, I am forced to rely on the time-honored earbone method of speaker evaluation. Cymbals better sound like cymbals and not like someone shhsh-ing into a microphone. There should be no muddiness in the vocals on a well-produced record, and unless the bassist is using a fuzztone, there should be no audible bass distortion.

My two La Scalas meet these tests admirabiy at both low and high volume. I used to think it had something to do with their size, that in smaller speakers the sound gets all strangled up for lack of room and comes out sounding choked. Nonsense, professional recording folk have told me. They’ve taken pains to explain about horn loading and intermodulation distortion and 32-foot bass waves and every other goddamn thing – all in this sad, condescending tone – until I got the distinct impression that, in their opinion, I had hooked up my amp to a pair of Rembrandts when the best I deserved was Keanes.

But the professionals had other more interesting stories to tell. The speakers were made, not on the East or West Coast, but in Hope, Arkansas, a tank town of the first water. They were invented by a fanatic scientist and audio legend in his own right, Colonel Paul Klipsch. The Colonel, it was said, was irascible and took God’s own sweet time making his speakers. He was supposed to be a pilot, a marksman, a millionaire and a mad genius . Estimates of his age ran anywhere from 70 to 105 years.

After years of collecting Klipsch stories, I finally managed to meet the Colonel. I have been to the City of Hope and my ears are open wide.

—

Hope, Arkansas, is located smack in the flat fertile groin of the Red River Valley, near the borders of Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma. It is 20 miles from nowhere, 30 miles from Texarkana and 90 miles from Shreveport. Truck drivers stop in Hope only long enough to see if there are any West Coast “turnarounds” to be had. (These are big black pellets of speed powerful enough, so they say, for a man to highball on out to the West Coast, tum around and start back in one sitting.) A nonfatal traffic accident is front-page news here and the miniature golf course is thriving.

Hope, named for the daughter of the man who laid out the town in 1873, has its own small measure of fame. Jim Bowie had a blacksmith hammer out the first Bowie knife in nearby Washington, and Hope itself, the chamber of commerce claims, is the home of the world’s largest watermelons. In 1935 Mr. Oscar D. Middlebrooks crossed him a big round watermelon with a big long watermelon to get a big round long watermelon that weighed 195 pounds. It was the largest watermelon ever grown on the face of the earth. Middlebrooks called it the Hope Triumph.

Lumbering, agriculture, poultry and light industry are big in Hope. Most of the townsfolk don’t really know what all goes on at Klipsch and Associates, out there a couple miles down the road in the tiny rural town of Oak Haven. ”Them hairy sons of bitches make radios, huh,” is a typical reply. Other people, only slightly more knowledgeable, mention the mad, wild lifestyle of the people at K&A. Some of the employees – executives, mind you – have been known to drink as many as two or three beers at raucous parties that last sometimes until midnight.

The 40-odd employees at K&A can well afford to snub their noses at conventions here in Hope. The average income for an individual wage earner in the county is $4200. The lowest paid man at K&A brings in $6200. Within three years, the same man will be pulling in $10,000. Job security is good. The Colonel’s first employee, Lloyd McClellan, hired in 1948, is still on the job. Almost no Klipsch speakers – ranging in price from the $250 Heresy to the top-of-the-line $1300 Klipschorn – are sold in Hope. K&A executives have no business contacts in Hope. There is no need to attend the right church, join the proper clubs or even behave in an identifiably sane manner.

The local Hope movers and shakers – the bankers, local merchants and big landowners — speak of the Klipsch folks as if they were some sort of strange and amusing sect with puzzling traditions. The most visible member – the living symbol of the sect — is Colonel Paul Klipsch himself. Stories.about him in Hope-town are legion.

“You know, he must be 70 years old and he runs by my house every day. Wears walking shorts. That man has muscles in his legs.”

“I saw him walking down the street one day and he was lifting his legs up over the parking meters, one after the other. Well, one of those meters was a little higher than the others and he cracked the inside of his ankle against the top. I heard words you wouldn’t hear in a Tijuana whorehouse.”

“I was on nursing duty when he was sick at the hospital not long ago and I remember I went into his room and he was up out of bed, running in place. He told me he had it all figured out, how many steps made a mile.”

“He’s the only man I know who has to tell you how a clock works before he can tell you what time it is.”

“Paul’s owned an airplane for about 20 years now, I guess, and this must have been right around the time he got the first one, because he was still experimenting with it. I was at the airport and I looked up and I saw a plane in a position no aircraft should be in. When he came in I asked him what the hell he was doing up there. He said that he asked a lot of people what would happen if he put the plane in stall position with the engine on and no one could tell him. He had spent the whole afternoon finding out for himself. He had a couple of sheets of paper all filled up with graphs about it.”

“He’s a pretty eccentric one all right and we like to laugh about him, but I’ll tell you one thing: I don’t believe there is a thing in the world Paul Klipsch couldn’t do if he put his mind to it.”

Bob Moers is president of K&A (Klipsch is chairman of the board}. In his 13 years in Hope, Moers has had occasion to collect some of the best inside Klipsch anecdotes. His favorite is the time the Colonel bought himself one of those pocket calculators. Seemed that the instructions warned that a certain element failed in extremely warm weather. “I came out to the office after lunch and it was a sweltering day,” Moers remembers. “Paul was in his lab and he had the air conditioner off. It was probably around l 00 degrees and he was standing there, sweating in his underwear, with the calculator in parts all around him. By the end of the day he had figured out why the part failed and sent the company a letter about it.”

Moers showed me around the small, L-shaped factory. They were making La Scalas and Klipschorns that day. A K-hom will weigh 225 pounds and stand over four feet high. They are all hand assembled, and some 59 boards go into the bottom alone, along with three-quarters of a pound of glue and two gross of screws. There are only four people in the world who can construct a K-hom bottom. If you want a Klipschorn direct from K&A, the current wait is 12 weeks. This fall they are moving to a new half-acre facility that should quadruple production.

We moved to the far end of the factory where a wide shipping door opened out onto the rolling green fields. In the distance one could see an older car, a 1956 Ford station wagon coming down the highway, kicking up dust.

“That’s Paul,” Moers said.

“In a ’56 Ford?”

“Well, Paul has made his million, but he’s almost pretentious in his unpretentiousness.”

The car rattled to a brisk stop in the lot and Paul Klipsch unfolded out of the driver’s side. He was straight and flat bellied, six foot three and 170 pounds. Someone in Hope had told me that he looked like “a typical Yankee.”

“How’s that,” I had asked.

“You know, like those Uncle Sam-wants-you posters.” Sure enough, Klipsch did have much of that same stern facial angularity. He wore a long goatee and his silver hair was combed straight back from the forehead. He was an imposing-looking man.

“How old is he?” I asked Moers.

“He just turned 70.” Klipsch looked a good decade younger. He wore a short-sleeved shirt, a creased Silver Bell western hat and odd-looking faded brown slacks. Moers whispered, “Paul buys his pants with a 34″ waist, then has them taken in two inches, but only at the waist. That way he has room in his pockets for all the crap he carries around.”

“Like what?”

“He has a journal that he has kept since he was at Stanford. Part of it is graphs for things he can’t carry in his head. He calls those graphs ‘dirty pictures.’ The rest is comments on experiments, and some of the rest is coded personal material. I think l’m the only person who can read the code, and I think Paul is probably the only man in the world who can tell you whether he was constipated or whether he scored on any given day 40 years ago.”

Moers and I had wandered back into the main section of the factory where we almost collided with the Colonel as he burst through a side door. Moers explained that I was a reporter here to do a story on Paul Klipsch. Paul Klipsch nodded absently and asked if I wanted a plane ride down to the airport in Shreveport. I explained that l would be staying for a day or so and hoped that we’d have a chance to sit and talk. Without so much as a nod, the Colonel turned, strode back toward his car.

“I hope you’re not insulted,” Moers said.

”No, not really. He seemed to have something on his mind.”

“I should warn you about something,” Moers said. “Paul runs several miles a day, you know. His doctor just cut him down from five to three miles a day and he was pretty mad about it. Anyway, he can’t stand people who aren’t in shape. We were walking down the street one day and there was a 250-pound woman in front of us and Paul muttered something about that ‘amorphous bag of suet.’ What I’m trying to say is that he tends lo say exactly what he thinks. He’ll probably comment on your … corpulence.”

Corpulence? There was a moment of silence. Corpulence? I’m a little over six feet tall and weigh in at 200 pounds even. There may be ten or 15 pounds I could drop, but … corpulence?

Moers changed the subject. Did I know that there were only 2000 La Scalas manufactured to date. The La Scala, along with the K-hom, the Cornwall, the Belle Klipsch (a furniture-type La Scala) and the Heresy were the only speakers K&A made. Did I know that the La Scala was designed in 1964 specifically for Winthrop Rockefeller’s portable public address system in his gubernatorial race against Orville Faubus?

No, I said, l didn’t know those things. My pants felt a little tight.

We retired to the president’s office, a handsome wood-paneled affair, where Moers explained that the K&A motto was the word “Bullshit.” The Colonel usually has a pocket full of little yellow buttons that feature the motto in Old English script. Klipsch first settled on the company motto when he read an ad for a new loudspeaker. According to Moers, the ad made incredibly exaggerated claims about the speaker. Klipsch read the ad over several times, looked up and said, “Bullshit.”

Moers himself, it turned out, was a fairly cosmopolitan Yankee who had come to Hope in 1961. He had graduated from the University of Illinois with a degree in marketing, had worked for Procter & Gamble and the McCulloch Corporation and was the Boston-based New England district manager for Sunbeam when he started hearing about Paul Klipsch. “I was a hi-fl enthusiast and I had bought a pair of Klipschorns from Bill Bell, who was the top Klipsch dealer in the country. We got to be friends and one day I said, ‘Bill, you and this guy Klipsch must be making a ton of money.’ Well, Bill told me it wasn’t that way. They needed sales help, Bell said, and he went on to sell me on the idea of at least visiting Hope.

“I was raised in Chicago and Boston and the idea or moving to Hope was repulsive. Of course I had never seen the place, but it was just after the ’58 integration battles in Little Rock. I thought, My God, I’m going to the land of segregation and Sow Belly. I’ll be bored and hot. I’ll have no social intercourse or intercourse of any description since my wife threatened lo leave me if l moved lo Hope. I did convince her to come down with me and I convinced Paul that I didn’t boost sales to a certain amount within a certain amount of time, I’d tip my hat and be on my way. I’ve been here 13 years.”

Moers and Klipsch are a good example of the time-honored symbiotic relationship of the businessman and the engineer. Klipsch himself often says, “My company went broke; Bob Moers’s company made money.” In 1960, the year before Moers came to Hope, K&A did $57,000 in gross sales. In 1973, the figure was $1.6 million, and projected sales for ’74 top the $2-million mark.

Paul Klipsch, as I was to discover, has a habit of drifting off into eye-glazing technical tangents. He never seems to notice that he has lost his listener, five or ten minutes before, on the brisk definition of frequency distortion. It is Moers’s job to make the Colonel’s work accessible to the majority of us who are technical cretins.

As Bob Moers describes it, then: The Gospel according to St. Paul.

In the beginning was the word. As spoken, it was difficult to hear over a couple of hundred yards. Then there was radio, and the vacuum-tube amplifier. Hard on their heels came Paul Klipsch. A teenaged Klipsch built his first radio the year before the first public broadcast, and in 1919 he made his first·loudspeaker with a mailing tube and a pair of earphones. Klipsch says those first speakers ”sounded like hell.” He attended “Cow Collich” (as he insists on·naming and spelling New Mexico A&M, now known as New Mexico State University), then got a job with GE at their test engineering plant in Erie, Pennsylvania, where he fell in love with some locomotives bound for Chile. Klipsch wrote the Chilean company and got a job maintaining those locomotives for four years. While in Chile he sent for his wife-to-be, Belle. He met her ship at a north Chile port and the two were married at sea.

Klipsch returned to America at the depth of the Depression and did graduate work in electrical engineering at Stanford. Later he was a geophysicist in Houston. “It’s interesting to note,’ says Moers, “that Paul holds more patents in geophysics than he does in audio.” In 1938, as part of a long-standing hobby, Paul built his first Klipschorn – which he described as “sounding like hell.” He worked on the unique design, publishing a paper in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America in 1941, and was granted a patent on the speaker the same year.

The war interrupted Klipsch’s work on his speaker. He joined the service and became second in command at the Army Munitions Proving Grounds (since closed down) in Hope. A long-time marksman, Klipsch invented and patented two accuracy devices for small-bore weapons. After the war Klipsch remained in the reserves at Hope where he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Between 1945 and 1948, Klipschi worked in a ten-dollar-a-month shed, improving his basic design and writing more technical papers about his experiments. At the time he had one other employee and was building speakers for other scientists and wealthy audiophiles. Belle Klipsch worked as a schoolteacher in order to keep food on the table.

By 1950 Klipsch had a few representatives in hi-fi stores around the country. By 1960 Klipsch had sold about 1200 of his Klipschorn speakers. With Moers’s help, Klipsch has now sold some 6000 Klipschorns.

Sometime late in the afternoon the Colonel arrived back from Shreveport. He bustled through Moers’s office into his own. There was the sound of some rustling, then he was back with a strange gadget which he handed to me. It was a standard hacksaw frame, but where the blade would be, there was a chain. A totally useless tool.

“That’s an Aggie chain saw,” the Colonel explained. He went back into his office. Thirty seconds later he was back to tell a joke. It was about this Aggie (defined as any agriculture-and-mechanical-school graduate, such as Paul Klipsch) who wanted to be a lumberjack. The foreman of the lumber crew told the Aggie he could have a job if he could cut a certain amount of trees with a power saw. At the end of the day. the exhausted Aggie was back. He had managed to meet his quota. “Let me show you something,” the foreman said. He pulled the cord and the power saw roared into life. The startled Aggie jumped back in terror. “What’s that noise!” he screamed.

So much for the jokes. The Colonel scooped up the prototype Aggie chain saw and disappeared into his office. Momentarily he was back again, this time with a faded yellow cardboard prototype of a Klipschorn speaker. It was dated 1940 and there was a patent number on it. The Colonel went back into his own office. The small cardboard box had one clear side through which one could see the way the 59 bottom boards fit together.

As I understand the problem and Klipsch’s solution:

The horn is the most efficient and effective system for reproducing sound. The problem is that in order to produce the full range of bass sounds. the horn itself must be the size of a small room. Klipsch developed a method of folding a horn in a trihedral comer in such a way that the boards inside the box acted as an exponential horn, along with walls of the room. For this reason a Klipschorn must be placed in the corners of the room. The walls are extensions of the exponential horn. The K-horn is still a mammoth speaker, but it manages to produce (on a single wall of power if one likes, the beasts are so efficient) the lowest bass note the ear can hear.

During the next few days, I had the opportunity to talk to the Colonel at some length, for all the good it did me. The conversations teetered on the brink of total noncommunication.

“Did you get interested in loudspeakers because you loved music or because you loved acoustics?” I asked.

The answer started well within my range of competence, then rolled on out into my personal twilight zone. ‘”A little of both,” he said. “I shouldn’t ever call myself a musician but I did play cornet in the Cow Collich band. Anyway, it was 1933 when one of my colleagues at Stanford invited me to his house. He asked me if r wanted to listen to the radio and I said, ‘Oh, heck no.’

“Well, he turned it on anyway. Jim Sharp had built a loudspeaker using a Jensen auditorium speaker and he had put a baffle on it. Well, baffles weren’t very well known then but they should have been, because in 1877 Lord Rayleigh described mathematically the function of a piston vibrating in a hole in an infinite wall. He didn’t call it a loudspeaker, of course. Making that thing speak and spout music wasn’t possible until we got ahold of something like a vacuum-tube amplifier, but the principle is the same as a paper-cone loudspeaker vibrating in a hole in an infinite baffle. By the way, an infinite baffle would be a wall of very large extent and not a finite box. Referring to a box as an infinite baffle is an oxymoron at best.”

Infinite baffle, indeed.

If there is a key to the Colonel’s character, I couldn’t sort it out of some 100 pages of tape-recorded transcripts of his own words. He tended to be guarded about his personal life, and unremittingly scientific. His story is best told in a few anecdotes.

For instance: Paul Klipsch is a devout Christian who sometimes takes notes during a minister’s sermon, the better to remember the Holy Word or, more often, to confront the preacher on his interpretation of Christ’s teachings. It is said that some ministers get exceedingly nervous when Paul Klipsch takes out his notebook during services.

A few years ago, the Colonel was chosen as a deacon at the First Presbyterian Church in Hope. To become a Presbyterian deacon, one must make a lengthy confession of faith but Klipsch balked on the third chapter, the one about how certain people are God’s elect and destined for heaven, while others are willy-nilly doomed to hell. The Colonel not only refused his deaconship but joined another church. It seems that Paul Klipsch believes that there is nothing a man cannot do, and that includes choosing heaven or hell.

Another story illustrating the same point: In the summer of 1969, at the age of 65, Paul Klipsch fell sick. For three months he battled a severe fever and the ailment was diagnosed as severe bilateral emphysema. Forty percent of his lungs was destroyed. Many men that age with a disease that serious might have resigned themselves to a few more sedentary years. Not Paul Klipsch. As soon as he could walk, he tried to run. At first he could jog ten seconds – total – at a clip. Within a year he had run his first complete mile.

Klipsch took up aerobics, a system developed by Dallas physician Kenneth Cooper, specifically designed for strengthening the heart and building up the volume of air the lungs are able to handle. Cooper recommends that a young man in good shape should exercise enough to earn 30 aerobic points a week. Klipsch usually earns 80. Dr. Cooper tested the Colonel recently and discovered that his vital capacity is now 110% of that of other men his size and weight.

During my visit to Hope, I happened to catch a glimpse at Klipsch’s notes for one day. Most of it was graphs and technical data, but it began like this:

R.1.8

S

R.1.8

Which, I’m told, means that Klipsch ran 1.8 miles, stopped in his house for a bowel movement, then ran another 1.8 miles. The total running time for 3.6 miles was 34.30 minutes – a distance and time that would challenge the average 30-year-old.

My favorite Paul Klipsch story happened almost two decades ago, in 1956 to be exact. The Colonel was sitting in a Philadelphia bar drawing dirty pictures. With him was the local distributor, a man who made part of his living explaining the comer speaker and the exponential horn to awed and wealthy customers.

“What’s that you’re doing?” the man asked.

Klipsch explained that he was designing a small speaker that could be used between two Klipschorns in a three-speaker array.

“But Paul,” the distributor argued. “that isn’t a corner speaker. You can’t do that. It would be heresy.”

“The hell I can’t,” Klipsch said, “and that’s what I’m going to call it.”

The next year K&A began marketing the Heresy speaker. It sells well to smaller churches in need of quality sound reproduction.

—

On my last day in Hope, I talked to the Colonel at some length and it went somewhat better.

“What induced you to puddle around with radio?” I asked.

“Well,” he said, “can you imagine a kid of seven or eight being impressed by something real noisy? That was what got me interested in locomotives and airplanes. My father took me to visit the local radio station at Purdue where they had a transmitter of the type known as the rock crusher. A rotary spark gap. When they put the key down, why all hell broke loose around the electrodes of this rotating wheel and it was noisy. Well, that was my first impression of a radio and I thought, I’d like to have something that would make a noise like that.’ Hell, you could hear it probably about as far as you could hear it.”

“Paul,” I said, “Bob Moers once told me that you didn’t have any interest in the space program and he found that strange since you have a plane and are a scientist and have an interest in the military. He thought it was perhaps because you have contributed to everything you’ve been in – geophysics, ballistics, audio – and that it was impossible for you to contribute in the same way to the space program. But you know, I’m thinking that everything you’ve done has had to do with noise, and space has to do with infinite silence.”

“You might have a point there,” the Colonel allowed. His mind seemed to be somewhere else and when I told him I’d be leaving the next morning, he wordlessly handed me a half-dozen bullshit buttons and an aerobics book. The last I interpreted as an unspoken comment on my corpulence.

In the week that followed I listened to my La Scalas and thought a bit about the man who sells Heresys to churches. The buttons said “Bullshit.” The book, in its way, said, ”The hell I can’t.” There is, I suppose, some kind of inspirational message there. For what it’s worth I’ve been playing a lot of handball lately and the last time I weighed myself, I had lost five pounds.

– 30 –

Couple of fun final notes: Paul Klipsch is no longer the most famous man from Hope, Arkansas. Another man from “a place called Hope” would become the 42nd President of the United States in 1993. And how about that early shout-out to aerobics? Cooper’s teachings were still far from mainstream in 1974.

Of course, we have to end with the classified ads, which has something for everybody. One of the more popular segments of the classified section was Prisoners’ Dialogue, where the incarcerated could request that Rolling Stone readers write to them while they were in the slammer. What’s especially unusual about this issue’s list is one name in particular …

Yup, that’s disgraced Watergate co-conspirator Chuck Colson, former special counsel to Nixon and the first member of Tricky Dick’s administration to do time. By this time, Colson had become an evangelical Christian, so his reply to you might well have been him witnessing to you to put down that evil Rolling Stone and pick up a Bible already. Who knows? I just thought it was interesting Chuck was looking for penpals.